Things I remember

In a high chair in the kitchen on Floyd Street.

Hearing the junkman’s cow bell ring from his horse drawn wagon

Pooping in my pants in 1st grade at P.S. 26

Not pooping in my pants at P.S. 57

The principal at P.S. 57 was Miss Head. Her dress was black and ankle length

Hearing about the bombing of Pearl Harbor on the radio

Waiting for the bombs to fall on my school while I was under the desk

Going to P.S. 25 when P.S. 57 closed

My Mom walking home from Dekalb Avenue carrying groceries in both arms

My Dad’s chicken store was on Dekalb Ave.

My Mom and Dad working in the unheated store with the doors wide open in the winter.

The chickens were dead but still with feathers and guts.

The chicken store smelled awful

Mom and Dad taking off their chicken-lice infested clothes in the foyer.

My Dad soaking in the hot bathtub Friday, in the late afternoon

He would fall asleep in the tub while I gave an account of my week.

The whole of WWII.

Every guy over age 18 was in the armed forces. Some didn’t come home.

Living with my grandmother for 3 weeks when my Mom was in the hospital.

Probably the worst 3 weeks of my young life.

My Dad losing his business and getting a job, working at the Brooklyn Navy Yard

My Mom always worried about something

Poor Mom, never really enjoying ……………..

Rationing, food and gasoline. No new cars for four years

I was 11 years old and I took the subway (2 trains) to the Bronx by myself

All the relatives lived in the Bronx

The war happened between my 9th to 13th birthdays.

Uncle Aaron and all my male cousins were drafted.

Radio was just as exciting as TV is now

Radio had Captain Midnight, The Lone Ranger (and Tonto), Jack Benny,

Fred Allen, The Shadow and 15 minute “soaps” every morning and afternoon.

Hershey Syrup was rationed and I couldn’t drink my milk without it.

Many summers in the Catskills (2 weeks at a time)

Greisberg’s was our main Catskill destination. It was near White Lake.

Almost all of the Tantas and cousins vacationed at Greisberg’s. The Uncles came up on Friday evening and left on Sunday afternoon

Each family had a room. There was a common kitchen from in which the Tantas cooked for their families.

Showers were located on a hill about 200 feet away from the bungalows.

I was among the male cousins who peeked through the cracks of the wooden showers shack while the other gender showered.

Greisberg’s was fun

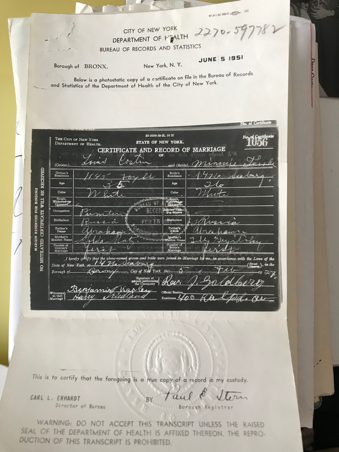

My Mom became a U.S. citizen in 1940

My mom had 7 sisters and one brother

My dad had one brother (never met him) and a sister named Ada

We knew that it was perilous to be a Jew in Europe.

Some of my uncles still had family in Europe. When the war finally ended there were almost no survivors among my Uncle’s families.

By some great miracle my aunt Fannie (Mom’s oldest sister) did survive along with her daughter and two grandchildren

They came to the U.S. in 1959

The war ends and I become a Bar Mitzvah.

June 1945, I get a job. Working for Joe Horowitz. My first pharmacy job.

June 1945, I graduate from P.S. 25 and go to Boys High in September

I think my dad’s brother may have been a bootlegger in Detroit, I’ll never know

My job paid twenty five cents an hour and all the ice cream I could eat

Loved working.

I always had some money in my pocket.

Mom and Dad were not happy with my fiscal independence.

I opened a bank account. I was 14

When I closed the account 10 years later the signatures didn’t match.

The job came with a bike. The bike was stolen . I should have chained it when I used it.

My boss bought a new bike and I had to pay for it, a dollar a week for 39 weeks.

That bike was among my best experiences. I rode it all over Brooklyn.

Even rode to the Bronx one summer. I was too tired to ride back. Dad came and picked me up.

I followed the route that he did when he drove to the Bronx.

After the war (WWII), Dad went back in business. He bought a huge 1932 Packard with a rumble seat.

It had 10 cylinders and smelled like dead chickens after a few weeks of hauling dead chickens.

Marvin and I had to sit in the rumble seat (in all weather conditions). Only room for 2 inside the car.

We froze in the winter.

Thankfully, it broke down and was too expensive to repair.

In 1940, we move from 346 Floyd Street to 412 Pulaski St. I was 8 years old

The move left Herby and Larry behind and I met Jerry and Gibby.

Jerry’s folks owned Gilman’s candy store (included newspapers and comic books).

Gibby lived in a fourth floor walk up with a common toilet in the hallway.

We moved from a one bedroom to a two bedroom apartment.

I shared a room with Marvin.

I read in bed before going to sleep, he couldn’t stand the light.

School was not my favorite place but the public library was.

On hot days the public library was the only place that was air conditioned

Sitting among the book stacks, reading about submarines. A whole summer of submarines.

Preparing for my bar mitzvah.

My bar mitzvah teacher was an ageless man with a short, tobacco stained beard.

He lived with his frail, little wife who served him endless glasses of tea while we labored over my Haftorah. Twice a week for what seemed forever, I repeated my haftorah portion

Finally, May 12, 1945, I became a bar mitzvah in a little shul on Hart St.

The Tantas, and Uncles and Cousins subwayed down from the Bronx en-masse.

Mom and Dad and Marvin and I travelled to Bronx every other week

The Bronx relatives rarely came to Brooklyn.

We did not belong to a synagogue. Dad was never a bar mitzvah and my Mom and her siblings' early life was too full of tumult, war and chaos for religion.

Religion aside, mine was a very Jewish environment. Relatives and friends and most neighbors were Jewish.

On the other hand, I was also surrounded by non-jews and non-whites. School was always an interfaith-interracial experience.

It was not always harmonious. Jew and non-jew fought and white vs black gangs prevailed

That was Bedford-Stuyvesant as I was growing up

Ironically, when the first Jews landed in N.Y. in 1654, Peter Stuyvesant tried to make their lives miserable,

All my friends, even the non-Jewish ones had parents who spoke in heavily accented English.

No one of my Bronx relatives had a car.

My uncle Aaron was an exterminator until he was drafted.

He used the GI bill to become an accountant and got a job with the I.R.S.

On hot days in the summer, we played cards in the alley between my building and the next. It was always shaded. We usually played blackjack with airplane cards used as currency

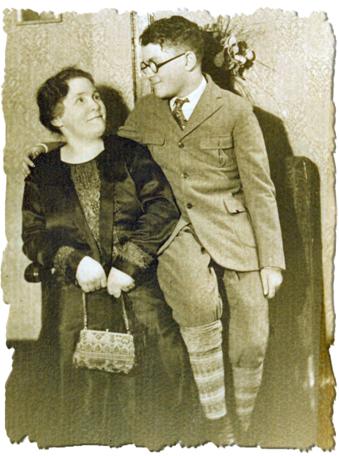

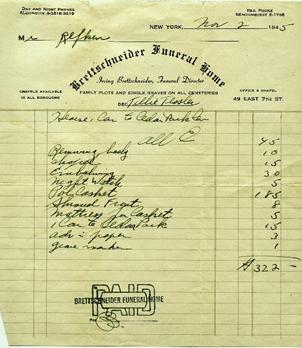

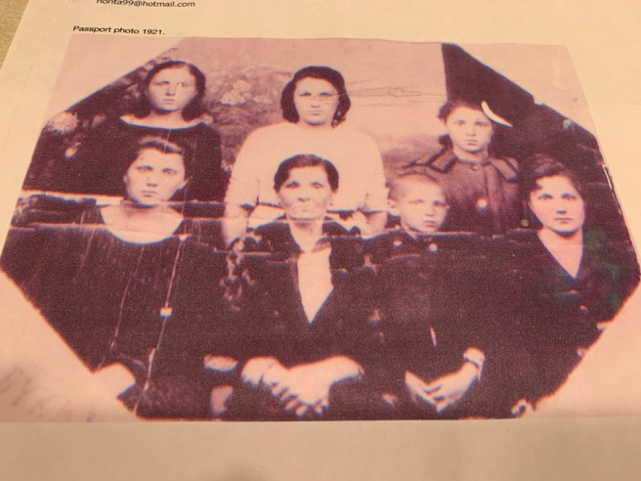

My grandmother (Baba) was an old, small woman who seemed to have been born that way except that I have seen her wedding photo. She was a cute, baby -faced bride.

Trolley cars disappeared and buses and diesel smoke appeared.

We had a refrigerator but many homes still used ice-boxes.

Where did the ice come from?

From Deep in a cellar in the building that housed the local tavern. A burly Italian man, using huge iron tongs hauled up 4-foot long blocks of ice and placed them on a wheel barrow-like wagon.

From the block of ice on the wagon, using an ice pick he broke the ice block into smaller blocks , put the smaller block on his burlap covered shoulder and carried it up many flights of stairs to a family icebox for 25 cents.

Airplane cards. During WWII a new brand of smokes appeared. Attached to each pack was a card depicting a different combat plane. The cards had the same value as baseball cards. They were traded, fought over and are probably among the treasures of the men who were boys in the early 1940s

Scrap books full of newspaper photos of the war. Maps on my bedroom wall (my side of the room).

Our clothes came from the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Any article of clothing that became orphaned became the dungerees, denim shirts and Pea coats in our wardrobe.

Hand me downs from my older cousins didn’t work too well. It seems that Marvin and I were just built wrong.

Dad was escorted home by a marine from the navy yard. He suffered from a welding flashburn to his eyes. He was ok in 2-3 days.

Gibby was Gilbert Hochberg. He was blind in one eye, the frames of his glasses were always scotchtaped where they had broken. One of his front top teeth was cracked. I’m partially responsible for the cracked tooth. We were both chasing an ice wagon for a free piece of ice, he slipped and fell on his face. I also slipped but was much less damaged.

Jerry was Jerome Gilman. His dad owned the candy store around the corner. Jerry always seemed to have a protruding belly, probably accented by a sunken chest.

Jerry & Gibby were a year older than me.

During the war, windows were adorned with small banners which contained blue stars. The stars represented sons and husbands and some fathers who were in the armed forces. From time to tim the banner contained a gold star. The gold star represented someone killed in action.

I now understand the great anxiety that filled the lives of almost every household.

There were 13 million men and women in the armed forces between 1941and 1945.

440,000 of them never came home.

Windows had to have blackout shades, car headlights were painted black on the top half of the lens.

When Pearl Harbor was bombed most people didn’t know where Pearl Harbor was located. Toward the end of the war a B25 bomber crashed into the Empire State Building. I could see the smoke from the roof of my building.

We had air raid wardens, air raid drills, and air raid shelters. No air raids.

Harry Lum (real name – Soo Hoo Jek) operated a laundry in one of the stores located on the ground floor of my building. He washed and starched shirts in his basement and spent all day, six days a week ironing those shirts. On Sunday, he dressed in shirt and tie and with a package usually tucked under one arm went off to Manhattans’s Chinatown.

Next to Harry Lum’s Laundry was a hair salon whose owner I never knew nor did I ever walk through its door.

Across from my home was Beth Moses Hospital. From about age 14 on, I would spend Saturday evenings in the hospital emergency room.

Horowitz’s Pharmacy was my home away from home for almost 4 years. Those 4 years shaped the rest of my life.

It reminds me of the the TV show ER. The pharmacy had a 16 stool lunch counter and most of customers were the doctors and nurses from the hospital.

The dispensing pharmacy was located in the rear of the establishment and had its array of chemical containers and pharmaceutical jars. The lab counter held an apothecary scale and various spatulas, beakers, graduates, molds and dispensing containers. This area was glass enclosed while on the other side of the enclosure, food was prepared for the lunch counter.

Our apartment was located on the first floor of a small apartment building. The building was diagonally across from the pharmacy.

At 2 A.M. a car crashed into the front window of the pharmacy. I heard the crash, looked out the window, and raced to my home away from home. Any delay on my part and the place would have been looted. It was just after my 15th birthday.

In addition to my boss, Joe Horowitz, there was another pharmacist, he was Julius Schwartz. He was a smallish, bald man with a mustache who complained about almost everything.

I usually worked Saturday until noon and after checking in with my mom went to the movie. Of course I had to take Marvin. Since most of my friends didn’t work, I selected one of them each week to come along.

It’s difficult to express the feeling of being 14 years old and having a couple of dollars in your pocket in 1946.

I never went to school with more that 25 or 30 cents. There were too many guys willing to separate you from your money.

There was a baseball game in the P.S. 25 school yard after school. I came with my baseball glove but was never picked for a team. So much for athletics.

Mrs. Scheiner in 5th grade is imbedded in my memory. She was so very kind to me when my mom was recovering from her second surgery. She must have recognized how disrupted my life was at that time.

Building model airplanes. Ten cents purchased an airplane kit. With a tube of glue, a single edge razor blade and colored tissue paper I assembled a 10-12 inch fighter plane.

For me, athletics were replaced with reading, model building, sketching and later on, writing.

My uncles were an interesting group. They were the men married to my mom’s sisters. Most of them were born in what was then Russia (including The Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia). My uncles emigrated to the U.S. as young men, leaving parents and siblings behind. Probably the most prominent reason they left home was to avoid being conscripted into the czar’s army.

The uncles all had some education and while all were Jewish, they were not religious.

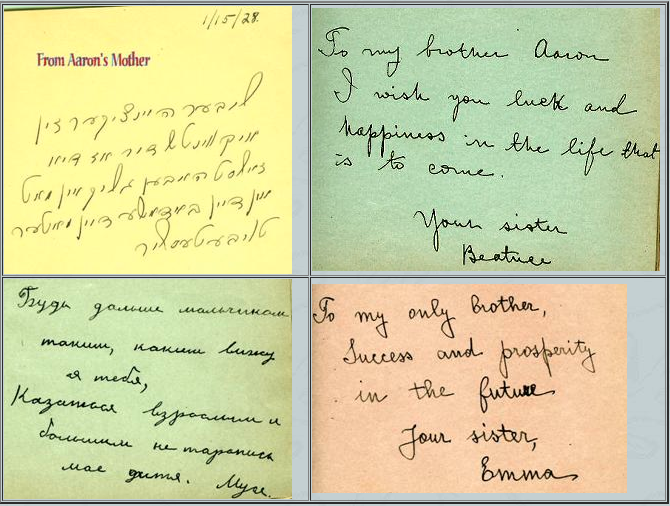

My uncle Aaron was mom’s youngest sibling and the only male among 8 sisters.

The telephone. We didn’t have one until several years after WWII.

Most people used public telephones located in various local businesses. One way to make some money, was to hang around telephone booths. When the phone rang and you answered, there was usually a request to summon someone who lived nearby. I would hustle, ring a bell or knock on a door and wait for the person to come to the booth and tip me a nickel or a dime.

The pharmacy had seven telephone booths and evenings could provide 50 to 75 cents in tips.

The store owner received 50% of the tolls deposited by callers. Seven booths probably paid the store's monthly rent.

Alone with my dad.

I was about 10 years old when my dad took me to the lower east side of Manhattan. I may have gone when I was younger, but it’s only from this point on that I can fully recall the experience.

We arrived on Delancey Street by walking across the Williamsburg Bridge. I stepped into another world and dad was my guide. Orchard Street, Henry Street, Hester Street and street names I have forgotten came off of Delancey like the tines of a fork.

The streets were lined with 4 story tenements built in the late eighteen hundreds. They housed the hundreds of thousands of immigrants (mostly jewish) who had swarmed ashore between 1890 and 1922. The front of the buildings contained the retail businesses that served the neighborhood. Most of the store signage was in Yiddish and most of the merchants were dressed as they might have been in the shtetls from which they had came. The stores, selling everything from clothing to food represented the more established businesses. Another merchantile layer was represented by the pushcarts that lined the curbs. Theirs was a mobile market for fresh produce and small every day needs.

This was the world of my dad’s boyhood. Every few yards we would stop while he related an experience that had occurred there. On Henry Street it was the ground level flat that he and his family lived in. When he was a kid, there was a fire in the building and his exit was blocked by the iron bars placed over the windows for security. A team of horses was used to pull the bars from the window to extract my dad. He had inhaled some smoke and had to be hospitalized.

The streets had an odor of their own. You could clearly smell the variety of foods, some sour and some sweet, intermixed with the aroma of horse shit.

At one of the corners of Pitt St. my dad paid homage to his mother, the grandmother I can’t remember. Here on the street, in the space she rented from the store owner, my grandmother had several barrels of herring which she sold for one cent each . In summer and freezing winter she would immerse her hands in the barrel to consummate a one cent sale.

Dad was absorbed with pushcarts that sold used, cheap tools. All his life my dad loved tools.

We passed barrels of pickles and I was sure to get a new pickle to hold me over until we got back to Delancey for a knish. My dad was not much of an eater but I think he enjoyed watching me eat.

Somehow, amid a deafening cacophony of sounds, motor vehicles managed to squeeze between the pushcarts as they pursued the more spacious streets.

The pushcarts are gone now. Many of the building are still there but the sounds now have a Latin flavor and the stores are owned by newer generations of newcomers. Not many pickle barrels left.

Robinson Crusoe fascinated me.

I read this book several times, starting when I was 10 or 11. It was written over 200 years before I was born but it resonated with me. I have never quite figured out why.

The 1939 Worlds Fair was in Queens and we all went. I ate too much cheese at the Kraft cheese display and was sick all that night. I saw my first TV set there. We didn’t own a TV til 1952.

About my mom.

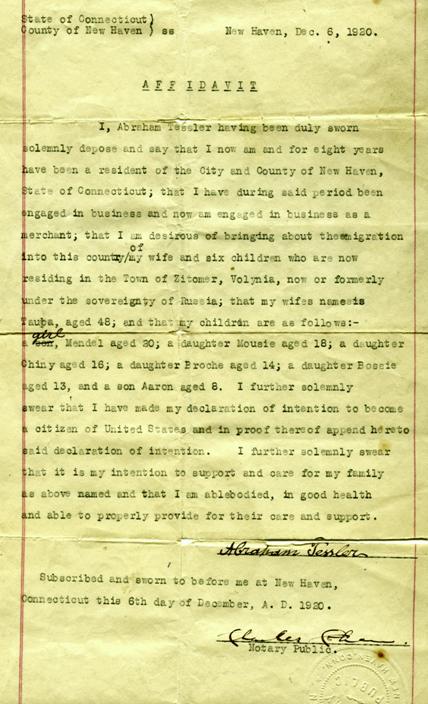

My mom emigrated to the U.S. in 1921 at age 13. Her father, my grandfather Abraham Tessler, came to America in 1913 with his 2 oldest daughters. They were my tantas Lilly and Anna. My mother and six of her sisters and infant brother survived the first WW and the Russian revolution. They experienced hunger and disease (they all had typhus). My grandmother Tobia was a single mom with 7 children to care for.

I learned little about my mothers’s father other than that he died in 1925. It later became evident that he had led a double life. During the time between 1913 and 1921 he met a woman in Harford, Conn and fathered a child with her. While he did eventually bring my grandmother, aunts and my uncle Aaron to the U.S., I imagine he was persona non grata thereafter.

My dad was an infant when he arrived in the U.S. His mother, my grandmother Rachael, also brought my 3 year old aunt Ada. My grandfather, Morris, was left behind in Russia with my dad’s oldest brother, Joseph. Rachael was not overly fond of her husband. When she could, she brought him to the U.S. in order to be reunited with her son, Joseph. By the time I was born my grandmother was suffering from dementia. I never met either my grandfather or Joe. Ada managed to live under the protection of a well-to-do aunt on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx.

On my 11th birthday I travelled from my home to the Bronx by myself. My poor mom thought she would never see me again.

Transportation was almost always a choice.

There were destinations that were obviously too far to walk. It came down to: should I spend a nickel (later a dime) on a streetcar or bus or should I walk and put the carfare to some other use. If I didn’t have to carry anything heavy, the choice was to certainly, walk.

I would direct my walk via a street that had store windows to gaze into. The best of these streets was Broadway, Brooklyn, with its El which ran from the Williamsburg Bridge almost to Queens. My part of Broadway was a treasure. It contained used book stalls, a huge stationary store (Rapoports), furniture stores which featured the first TV sets in the neighborhood, several movie theaters, newspaper stands with the latest magazines and comic books (you could slowly browse by and check out the magazine and comic book covers). Most of all, the neighborhood characters who seemed to congregate under the El. They were the Street people, men and women who spoke to themselves. I always wondered where they went in the coldest periods of the winter. There were no trees on Broadway.

The chubby shop.

I was a modestly fat kid. We caught the DeKalb Ave. trolley and went to Knickerbocker Ave. to the “chubby kids shop” where my mom would buy me trousers. The store whose name I’ve long forgotten was always full of moms and their fat kids (all boys). I always imagined that they didn’t get chosen for baseball games either. Why only trousers? Well, you could always wear a hand me down shirt after the sleeves were shortened. Sweaters and outer wear handed down from one of my older cousins could almost always be made to fit by down sizing, but not the seat of knickers or long pants.

Buying my bar mitzvah suit required the services of the family specialists. This involved my dad and mom in addition to at least one of my tantas. For clothing this important, the lower east side was our destination. Tanta Mussie met us on one of those streets where resided store after store of mens and boys clothing. Someone from the store would remain outside and urge shoppers to come into his store “ just to try on”. The cardinal error was to seem in the least interested in any of the offerings. We went into at least 4 or 5 stores, browsed while the owner tried to figure out what our objective was. He offered, wool, gaberdine, with a vest, two pair of trousers, wide lapels, or even a free hat. Finally, when the experts had zeroed in a suit, I had to try it on. At this point the “mavens” determined if there was enough room in the crotch, under arms and how well the jacket looked when it was buttoned. Could I wear it next year? Could Marvin wear it for his bar mitzvah (16 months later).

Next came the haggling over the price. For special customers like us and because it was for a bar mitzvah he would sacrifice his profit and let us have the suit for $29.00. But they were ready for

him and offered $20.00. After much going back and forth and with the suit laying on

the counter we turned to leave, when behind us we heard the exasperation in the voice of the store owner as he announced his bottom price, $23.50. My dad paid the $23.50 after reminding the suit seller that a hat was to be thrown into the deal. Did I ever wear that hat?

Ironically, in the next year I had grown 3 inches, the suit never fit Marvin who was even taller and skinny. But alas, five years later my cousin Irwin wore it to his bar mitzvah.

The sunflower seed machine at Gilman’s candy store was ground zero. It’s where I could expect to meet the guys. It was the focal point of our social life. All the while, old Mr. Gilman admonished us not to stand near the news papers and to make space for the customers. The very small piece of dirt adjacent to the curb and directly in front of the candy store was our marble court. Those round, multi-colored pieces of glass were our little treasures. They were the currency of the street.

We played simple games with them. There, on that dirt arena we did battle with our marbles (Imees) while we gamed with and traded them. I don’t remember ever buying any marbles.

The newspapers were The Daily News, The Mirror, NY Times, The Journal American and the Herald Tribune. In addition there was The Daily Worker and an assortment of foreign language papers. The Forward was read backward in Yiddish. There were at least 2 Yiddish papers, plus, Italian and Polish weeklies. My dad bought the Hearst owned Journal American. In retrospect, I don’t know why my very liberal father would buy the very conservative Journal. I guess I’ll never know.

I started to save stamps very early, certainly by age nine. For the 3 weeks that I spent living with my grandmother during my mom’s illness, the only reading material I had was a Scott’s stamp catalogue. Baba didn’t speak or read English and since my uncle Aaron was in the army, there was no english language reading material in her apartment.

The Scott stamp catalogue was sent free on request and I spent lots of time gathering envelopes from family and family friends and soaking off the stamps. Foreign stamps could be purchased in hobby shops. They came in packets and cost anywhere from 10 cent to 25 cents a pack. If I bought a pack (rarely) I would take out the stamps I didn’t already own and trade the rest with the other stamp collecting kids.

Stamp collecting eventually led to first day covers. This turned out to be much more satisfying. When the issuance of a new commemorative stamp was announced, I would send an envelope with correct coinage equal to the face value of the stamp, to the site of the stamp's place of issue. I would receive the envelope with the new stamp marked FIRST DAY OF ISSUE. It was exciting to find a new First Day Cover in the mail.

Gibby’s dad never had a job. Not a real job. He was the neighborhood numbers dealer. Even in this illegal gambling enterprise, he barely made a living. The minimum bet was 25 cents. Some people (men and women) played every day. The winning numbers were the last 3 numbers of that day's paramutual receipts at the racetrack. A dollar bet could bring a player a hundred dollars. I suppose at some point most consistant players won something. Certainly, the numbers operators won.

Eating out. We almost never did. However, when we did eat out, the choice was Chinese, Kosher deli or Vegetarian. Eating out with my mom’s family in the Bronx almost always defaulted to a vegetarian restaurant on Tremont Ave. As we grew older, me and my cousins rebelled. To quiet the rebellion, one of my older cousins was given enough money to take us to the Chinese

eatery down the block. This was the beginning of our eating emancipation.

Every neighborhood with a sizable jewish population had one or more delis. There was no competition, when the choice was a heaping pastrami sandwich with a side of potato salad and a fresh pickle. The kosher deli became to the neighborhood what the pizza parlor would become a few years down the line.

While spaghetti was part of the menu in our home, tomato sauce was not. Ketchup was our traditional pasta sauce. Ketchup is still great on eggs.

My summer in Woodridge N,Y.

In the summer of 1946: My dad and a not remembered partner pooled their resources and opened a chicken store to serve the summer vacationers in the surrounding bungalow colonies. Financially it was a failure but for me it was an extraordinary experience. For over two months we lived in a small apartment next to the high school in this 8,000 person (during the summer) village. The community was literally divided by railroad tracks that ran down the center of its main street. At one end of the main street was a saloon called the Kentucky Club. On weekendsit provided live entertainment. From a proper vantage point one could see the female entertainers changing into and out of their costumes.

In Woodridge, I learned to drive a very old Ford pick up truck. Stick shift.

Even though we had vacationed in the Catskills, 2 weeks at a time, this was real immersion into the jewish farm/small town culture. I saw the “Outlaw” with Jane Russell in Woodridge’s one movie theater. The small high school had a silver painted world war I cannon on its front lawn. Woodridge did not have a public library and the local news stand did not carry the Journal American.

Marvin and I arrived in Woodridge atop a pile of raw beef covered with canvas inside of a surplus war ambulance. The ride from New York City was 4 hours, non-stop.

The end of WWII: The war ended in the summer after my bar mitzvah.The boys who left a few years ago came back with little brass pins in their lapels. They were veterans and the pin (the ruptured duck) verified it. The little banners with the blue stars started to disappear. Home telephones became available, new cars were replaced on the assembly lines that had been producing tanks and planes. When I entered college in 1950, about one third of my class were veterans attending on the GI bill. I was 18 and some of my classmates already had teen age children.

By 1950 we were involved in another war. Korea.

I was draft deferred until I graduated from college in1954.

With end of the war in Europe, we learned of the toll the war had on the peoples of Europe,

Especially the 6 million Jews who died in the camps and unmarked graves in the woods and fields of eastern europe. Of 7 million jews in pre-war Europe, less than a million survived. It seemed ironic that I and some of my jewish friends would be sent to Germany as U.S. soldiers just 10 years after this holocaust.

Things sold in Horowitz’s pharmacy. Wets & Drys. The Wets were liquid, over the counter medication, usually filled from gallon containers and dispensed in 2 oz. 4 oz. and 8 oz. glass bottles. They were Browns Mixture, Stokes expectorant, Glycerin, Oil of Wintergreen, Coca Cola Syrup (supposedly for nausea), Syrup of Ipecac, Terpin Hydrate and codeine to name a few. The Drys. were solid, over the counter medications such as bicarbonate of soda, epsom salts, mustard powder (for mustard plasters), Seidlitz powders and stringed rock sugar.

Sanitary napkins were wrapped in plain brown paper or special gray or brown bags. Condoms were kept in a drawer behind the counter and quickly bagged for the man who requested them. Women did not buy condoms and men seldom purchased sanitary napkins.

For many neighborhood folks, the pharmacist was the first source of medical advice. Free advice was dispensed by Mr. Horowitz or Julius Schwartz in their starched gray lab jackets. The free consultation was usually accompanied by the sale of a medication to treat the patient-described ailment. On occasion, there was quiet but fir advice that a visit to the doctor was in order. The pharmacist was respectfully called “Doc” .

As early as I can remember, I knew that I would be a health professional. The college of Pharmacy which I often passed on the way to Boys High was part of my destiny.

About radio.

Radio of the 30’s and 40’s was like TV, the entertainment center of the home. In many ways more so. Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 7:30 PM on WOR my dad and I were glued to our 1935 model radio listening to the Lone Ranger. Sunday afternoon, at 2PM on WEVD was Yiddish language time, with my mom sitting intently, listening to Tsuris bie Lieten (peoples troubles). The program was sponsored by The Hospital For Incurable Diseases and my mother sat for 30 minutes crying her eyes out. Sunday was an important radio day. The Shadow and Jack Benny

were the evening’s premier shows.

Radio had the advantage of your being able to listen to the program and do other things as well. Much of my school home work was left for Sat. afternoon. The Metropolitan Opera On The Air played for 3 hours. Complete with Libretto the opera filled the silence of hours of less than enjoyable home work. The newspaper still provided the best source of news. People discussed the previous day's radio offerings in much the same way as TV shows are discussed today.

Sick days offered the radio soap in 15 minute segements, which ran 5 days per week for an infinite number of weeks. They were called “soaps” because so many of their sponsors were soap companies. Other major sponsors were cereal makers and oddly enough at least one coal company “Blue Coal”. With regard to the “soaps”, you could miss months of episodes and still not

lose the plot continuity.

Beth Moses Hospital was across from my building. Eventually, Gibby became the hospital elevator operator. The elevator was a cage with a fence-like door which was manually closed before the hallway door closed. During quiet periods I convinced Gibby to allow me to opereate the elevator. Great fun.

The hospital emergency room became my friday and saturday night hang out. I now realize how much I learned on those friday & saturday nights. I was about fifteen, and had been working at the pharmacy for almost 2 years. During that time I got to know the doctors and nurses who worked in the Emergency Room. When my curiosity nudged me to the ER, I was readily accepted as long as I watched, stayed out of the way and kept my mouth shut. I saw a lot of bloody wounds being treated and sutured and the delivery of a baby on a gurney as the mother was being wheeled into the ER. There were stabbings, gun shot wounds along with the effects of drug and alcohol abuse. Years later, in the army, in a battalion aid station I actually became the first responder to many of the same non-combat experiences as those at Beth Moses ER.

Our home on the first floor of 412 Pulaski Street, was small but comfortable with two bedrooms, one occupied by mom and dad and the other I shared with Marvin. The building housed 16 apartments. Some only had one bedroom. The living room in our apartment contained the usual , well preserved furniture which my folks covered with plastic zip on covers. The living room floor was covered with an oriental-like rug which was rolled up with camphor balls and covered in tar paper for the summer. It was placed in an upright position in one of our 3 closets. Consequently, our clothes required seasonal airing to rid them of the camphor ball odor.

With space at a premium, the apartment was purged frequently. Old or unused stuff was moved out to make room for newer stuff.

My room contained two beds, a set of drawers which matched the wood of the beds, a night table and lamp and finally a desk and chair. In order to get to the desk I had to climb over Marvin’s bed. Essentially, the desk and its contents were mine but Marvin controlled access. The desk was a repository of my treasures. It contained notebooks of things I had written while in high school and later during my college years. In addition, it contained some art works I had dabbled in and the various stuff I had chosen as keepsakes. When I came home from the army, my things were all gone.

During the almost four years that I worked at the pharmacy, I took on more and more responsibility. I don’t remember Joe Horowitz ever saying that I should do more complex tasks. It all evolved. From making deliveries and sweeping the floor, I was making salads in the kitchen section of the store. In a year or so I was bottling and packaging wets and dries. Eventually, I was placing orders for over the counter and toiletry items. During the summers I worked the lunch counter at lunch time. Pharmacy practice required doing many things which would appear archaic today. It was common practice then and for hundreds of prior years to compound medications. Pills were hand rolled, capsules were filled with mixtures of drugs. Most skin ailments were treated with ointments and creams which were prepared by the pharmacist. Individual packets of medicinal powders were mixed. In this era just before antibiotics, various liquids were mixed or drugs dissolved in liquids to treat what ailed you. I was fortunate in that Joe Horowitz and Julie Schwartz allowed me to assist in the dispensing process. Years later, when the rare occasion arose, I was able to hand roll a pill and mold a rectal suppository.

Among my mother’s sisters there existed a distinct hierarchy. Mom always needed approval from her older sisters. The sisters had established the rules and if you deviated, you were swimming against the current. At sixteen, with my own money, I went alone and purchased a sport jacket. With the sleeves shortened and the buttons moved a bit I presented myself to my folks. I know they liked the jacket but I could see the trouble in my mother’s face. How could I buy something as important as a sport jacket, alone? The Tantas would not approve. Over time, as my adult male cousins married and had their own children, their mothers still went with them when they purchased any important piece of clothing. That’s the way it was. But not for me.

Boys High School. No girls, no proms, wooden floors in a fortress-like building built in 1891.

Right through college, I always lived within walking distance of school. For me, graduating H.S. and going to Brooklyn College of Pharmacy was like going from the 12th grade to the 13th grade.

The principal of Boys High was Alfred A. Tausk. Asst. principal ‘s name was Hansen. They had both been student together at Boys High many years before (class of 1906).

Going to and from H.S. was a challenge. Some of us would assemble in Thompkins Park, midway between home and school and move in a solid block up Marcy Ave. A lone student walking up Marcy Ave. was an easy mark for small gangs on the prowl for easy prey. Going home was the same in reverse. Interestingly, there was a public library in the one square block that was Thompkins park. The library served as a sanctuary in the Bed-Sty neighborhood.

Mr. Papke was my 10th grade social studies teacher. He was a 300 pound giant who I grew to dislike more and more as the term went on. When he discussed the second World War, he inferred that we should not have come to the aid of the European nations that Hitler had overrun. At some point I stood and called him a Nazi. He ordered me to the office of the asst. principal, Mr. Hansen. Mr. Hansen asked me to apologize to Mr. Papke. I refused. He had me come back next day with my poor, confused mom. I had related to her what I said to Papke. As far as she could see I was challenging the school’ s authority and I was in big trouble. I tried to explain that Papke did not like Jews and was no better than the Nazis we had heard about. In the end, with a small rebuke Mr. Hansen transferred me to another social studies class.

About a third of Papke’s class was Jewish. No one challenged him.

As the holocaust revealed itself, I felt that only the accident of having been born in the U.S. spared me and my family. I was certain that if I had been in Europe between 1939 and 1945 I would not have survived. I probably was right, and I think it has been a defining event in my life. Like the bullet that just missed me.

The store across from Boys High was a hangout that sold great fruit pies. I almost never missed a day without either a lemon or cherry pie.

By 1945, Boys High was on split session. For my first year I went to school from noon to 5 PM. I usually got home by 6 PM, ate, and went to work until 9 PM two nights a week . On Saturday, I worked from 9 to 1. It seemed like a normal routine. I reserved Sunday for homework or school reports. didn’t think about it then but I must have taken great pride in the responsibilities I had at the pharmacy. I might have left some school work undone but never my duties at work.

I’m not sure when I started to collect National Geographic Magazine. I was certainly in my early teens. A subway ride to lower Manhattan around Wall St. took me to streets lined with used book shops, stamp and coin dealers and one shop that specialized in maps. I had a pocket full of coins and usually purchased an old NG magazine. They sold for five cents each. I browsed the collectibles in the various shops. It was like an unfolding show. I spent many enjoyable hours looking and enjoying. The Map store had, under glass, maps drawn hundreds of years ago. One map that fascinated me was of pre-revolutionary America in which much of the land west of the Mississipi was blank.

During WWII I had maps of the various theaters of operation on my side of the bedroom wall. After D Day I had colored pins that traced the allied advance from Normandy to VE day. The map of the Pacific war theater allowed me to follow the island by island victory over the Japanese. In August of 1945 I took the maps down. The war was over.

I spent a lot of “alone” time. I also spen a lot of time with my friends. It seems that solitary time was reading time and making things time. Not sharing time.

We did not have a washing machine or dryer or air conditioner. Mom was the washer and she hung the laundry on a line which ran from a hallway window in our apartment building to a pole in the back yard. The exception was my dad's dress shirts. They went to Harry Lum, the Chinese laundryman. Dad and his shirts went through a ritual. He wore a shirt and tie on our almost weekly trips to the Bronx. He would undo at least 3 shirts from thei laundry packaging and try on each one until he finally made a selection. Choosing a tie followed the same routine. The tie pin selection was a bit less arduous. We were usually all dressed and waiting for dad to make his shirt, tie, and tie pin selections.

Those were the good old days, if you accept that they were harder-life days. No washing machine or dryer. Work for my mom and dad in the unheated, bitter, cold chicken store. Feathers and chicken intestines put bread on our table. Mom's walk from Dekalb ave. with heavy grocery bags were all life shorteners. Among the things lacking in the period after WWII were all the medication and diagnostics which have contributed to longevity and quality of life.

If we mourn the absence of TV and the internet, think about not having CAT scans, MRI’s, sophisticated blood analysis, an array of broad spectrum antibiotics, anti-hypertensives, Cholesterol reducing drugs, oral anti-diabetics. antivirals, powerful pain reducers and wonderfully trained medical professionals.

Dad was never a bar-mitzvah. He couldn’t read Hebrew and we never belonged to a synagogue. He spoke yiddish with mom and felt most comfortable with other Jews. My dad was five-five and never weighed more than 145 pounds. He worked hard from childhood, and probably never had a warm, affectionate moment with his parents or his brother or sister. If I had been an athlete, he probably would not have attended any of my games but I always knew that he took pride in my accomplishments.

The Korean war: Within 10 years, the U.S. was plunged into 2 wars. This war involved hundreds of thousands of men who had been too young for WWII and many veterans of WWII were recalled to fight in Korea. College kept me out of Korea. I entered the army in October 1954. The war was all but officially over. In my 2 years in the army, many of my fellow soldiers were veterans of both WWII and Korea.

Fort Dix was my first experience with the army. From the reception station on Whitehall St. in N.Y., we were bused down the NJ turnpike to Fort Dix and basic training. Just behind me as we were assigned serial numbers, was my pharmacy school classmate and soon to become army buddy, Art Weisbart.

For the 18 and 19 year olds (I was 22 at that time) basic training was a breeze. For me it was mere survival. At the end of 8 weeks, I had survived and was 27 pounds lighter. Walking back and forth to school had been my most strenuous exercise. We had, what seemed to me, a cruel sadistic drill sgt. We double timed (ran) almost everywhere, rain or shine. Chow time was limited to waiting on line, gulping down food and out again to double time to wherever.….. I still fold my clothes in the way we leaned back in basic. I did fulfill my gun shooting fantasy. I’m not sure if I ever hit a target but I did qualify on the M1 garand, M1 carbine and I threw a live grenade. The rifle range at Ft. Dix was in the most isolated part of the camp. My days on the range were

probably the coldest of that winter. The sandy soil was frozen solid and the firing position was prone on what seemed like razor blades. When a few snow flakes fluttered down I thought shooting would end and we’d all get on trucks and head back to the barracks. No way. As long as we could see the targets 300 yds down range we stayed.

K.P: Eventually, my name appeared on the K.P. roster. I tied a white towel at the foot of my bunk and was roused at 4 A.M. I spent the next 15 hours scrubbing pots and pans. The next time my name appeared on a duty roster, I was trucked to the army laundry building where woolen blankets are washed and dried. A wet, woolen blanket weighs 3 times that of a dry one. They are hand transferred from washer to dryer. There were thousands of them. We did that little chore for

10 hours.

Uncle Sam issues each soldier dress uniforms, fatigues, underwear, socks and boots. Boots seem to be the army’s greatest concern. Your uniform may need alteration, but your boots (2 pr) must fit.

I gained a lot self confidence in the army.

The two army years were thinking years. Periodically I thought about how my post army life would unfold. Without knowing how, when or where, I envisioned a life away from New York City. I imagined myself in a rural setting. I guess the summer in Woodridge and my being stationed in rural Nuremberg set the stage for my small town future.

I seem to have passed over my Pharmacy school experience. I had a genuine dislike for Brooklyn College of Pharmacy. I was a lousy student and the courses were boring. The school was small. A single building on Lafayette Ave. No campus. I failed 2 out of 5 course in my sophmore year and

I had to repeat that year. It was a sobering experience.

Dean Schaeffer suggested that I was wasting my parent’s money. When I told him that I was working and paying my own tuition, he mellowed a bit and wished me luck. The repeat year was easy and I managed to pass all of my courses and graduated. In June 1954, I took my N.Y. state boards and passed. Ironically, about 20% of my classmates had to repeat the exams.

I guess that my college experience is linked with my after school / weekend job. During my sophmore year I replied to an ad for a position at the St. Catherine Pharmacy. The pharmacy was owned and operated by Mario Furia. I worked for Mario for 3 years. He was a little guy, barely 5 feet 4 inches with a graying mustache. He traveled every day, 7 days a week from Newark N.J. to

the pharmacy on DeKalb and Vanderbilt. Mario was very kind to me, often ordering something for me to eat when I arrived from school. In addition he usually loaned me tuition money which

I repaid during the summer.

I could write a book about Mario Furia. He became a pharmacist during prohibition when only pharmacies could sell alcohol on a doctor's prescription.

Just as I had quickly assumed responsibility at Horowitz’s pharmacy, I easily took my place with Mario. During my work time I dispensed most of the prescriptions. Much of what I had learned as a teenager at Horowitz’s plus pharmacy school made it easy at St. Catherines.

The neighbothood in which the pharmacy was located had some unique qualities. It was the seat of the catholic archdiocise. There were several convents, a catholic High school and lots of nuns and priests.. At the same time the area had a very Italian flavor with an assortment of illegal activities. Numbers, prostitutes (we were 4 blocks from the Brooklyn Navy Yard) and a variety of

gambling establishments and after hours drinking holes.

The Piro brothers were the undertakers across the street. Being well connected, most of Fort Greene’s dead ended up at Piros.

Mario’s pharmacy was the only catholic owned one in the area so the health needs of most of the Italians /catholics came through our front door. It never occurred to me that we conducted anything but normal commerce. Two blocks north of the pharmacy on Clinton St. were the doctors offices and the homes of the rich and politically elite of Brooklyn.

I look back now with nostalgia at the hundreds of characters I met in Mario’s Pharmacy.

Woman's panties were called bloomers. Boxer shorts were the norm for men's underwear.

Electric razors left your face raw and red.

Navy Dungerees had button flies.

Many of my classmates were never drafted. With the Korean war over, the need for large numbers of draftees ended. When I applied for pharmacy positions, I was asked if I had been in the service yet. Many prospective employers reckoned that hiring a potential draftee was not good business. I went up to my draft board and asked when I would be called. They were rather vague about a date but gave me the option of selecting a date, so I did. That’s how I I became a soldier on October 14, 1954.

Wow, I’m recalling so many experiences, that I’ve passed over my two summers as a bellhop at Sha-Wan-ga lodge near Bloomsburg N,Y. Sha-wan-ga was a summer resort that catered to mostly young families and young singles. I met the two Stans. Stan Kauffman later to become a professional dancer named Stan Kay) and Stan Brandt. Both guys were a year older than me and worked as Bell hops in Miami during the winter, and in the Catskills during the summer. They

were about 19 years old and each had a car and the sharpest clothes I’d ever seen. The girls seemed to fall at their feet. To my simple, undeveloped precortex brain, theirs was the life for me. I told my parents that I was going to quit school for a year and bell hop with the two Stans in Miami. The news was so devastating to my parents that I had to put my brain in reverse and purge my

mind of the idea. That’s how I did not become a professional bellhop. The two Stans went on to other careers as well.

I had a great time at Sha-wan-ga. I made enough money for one year’s college tuition. I also met Sally Weiner. It was like hitting the female lottery jackpot. Both summers at Sha-wan-ga were female heaven- packed.

Recently, checking a map of the region where Sha-wan-ga lodge had been located. I found a road called Sha-wan-ga Road with housing and streets where the hotel and its out building had been.

To put things in order, it was after my second and final summer at Sha-wan-ga that I went to work for Mario Furia.

I never realized how much there is to remember.

I remember getting off the plane in San Antonio at 2 A.M. dressed in my army overcoat over my dress woolen uniform and freezing. By 6:30 A.M. I was standing in formation in front of my new barracks in my fatigues and still freezing. After chow, at 1 P.M. it was 80 degrees and I was actually sweating. This was Fort Sam Houston, Texas in January 1955. Fort Sam Houston was the destination for those of us who were to be trained as medics. My pharmacy degree only allowed me to apply for a commission. There were not enough pharmacy officer slots, so I would have to wait for an opening, then agree to serve two years from date of commissioning. My turn came exactly one year later in Germany and I had to say, “thanks but no thanks”. After all, I was already a Sp2, and almost a short timer.

The Jewish community of San Antonio was on a special mission. Those of us who were Jewish trainees were invited to a monthly bagels and lox breakfast. Trainees who were to be stationed there long term were prospective husbands for the community's Jewish daughters. Those of us who would be passing through only got the bagels and lox.

The many nights that I had spent at the Beth Moses emergency room made my training at Fort Sam a breeze. Though I had never done one before, starting an I.V. and giving intramuscular injections seemed quite natural to me. Some of my fellow trainees actually passed out when it was their turn to become casualties. The most difficult part of army medic training was evacuating casualties at night in darkness. This bit of fun and games took place in the high country near San Antonio. Real, live scorpions had to be shaken from boots in the morning and the daytime temperature was always in the 90s.

Unbelievably, I never had a telephone conversation with parents in my 2 years in the army. On the other hand, my dad and I exchanged letters almost weekly. I wish those letters had survived.

San Antonio was 150 miles from Laredo, Mexico, a honky-tonk border town which beckoned to G.I.s . It was my first time outside of the U.S. The border was wide open. Dressed in very casual civilian clothes and with our dog tags clinking around our necks, we just walked across the bridge from Nuevo Laredo in the U.S. to Laredo, Mexico. The poverty was palpable. Little boys came

up to us, hawking their sisters' sexual services. Silver trinkets were for sale very cheaply. Artie Weisbart and I had about twenty dollars between us. It was enough for our Mexican weekend for food lodging and a few trinkets.

Sunday at the Breckenridge Hotel, you could order all the shrimp you could eat for $2.50. Too bad. I didn’t like shell fish. Some of my Fort Sam buddies passed up breakfast in order to fill up on shrimp.

If you liked airplanes, you were in airforce heaven. With three airbases nearby, the sky was always buzzing with fighters, trainers and helicopters.

On April 4, 1955, we departed by train for New York where after a few days delay, we boarded a troop ship bound for Bremerhaven, Germany. I did get to see my mom & dad for a few hours before shipping out. I didn’t see them again for 17 months.

The troop ship was the General Buckner. It was an experience I wouldn’t ever want to repeat. For nine days, the odor of vomit was pervasive. If you rolled out of your bunk (stacked four high) you immediately stepped into 2 inches of vomitacious water. You had to get your boots on while you still in your bunk or your bare feet became immersed in yellowish slime.

Meals were served in such a way that you were on a line which wound up or down several decks. Breakfast could almost run into lunch. After eating you proceeded to the nearest barrel and vomited. By the second or third day, the seas became very rough and the ship rolled, leaving you in a constant state of nausea.

Once you rose in the morning and left the sleeping area, you were encouraged not to return until after supper. Ironic, because the only relief from the nausea and vertigo was to be horizontal. Actually, once on deck, with wind blowing and ship swaying, inhaling the sea air was somewhat remedial. I had to shift from one sheltered spot on deck to another in order to evade the wind gusts. Meanwhile, below decks, stealing of personal items was rampant. The only semblence of security was to padlock your duffel bag and suspend it from your bunk. In a brief moment of unawareness, my almost new field jacket disappeared. My only recourse was to snatch up the next unattended field jacket that I spotted. Showering was impossible. Hygienically, the best you

could do was wash different parts of your body at different times. The deck in the wash areas were far worse than the bunk areas.

On the upper decks were dependent wives, children and infants of army personnel who were eligible to have dependents with them at their duty assignments. There was no air transportation for dependents.

After 4 or 5 days on board, I started losing weight. Clothes fitted looser to the point where I had difficulty keeping my pants up. Debarking the ship, I held my duffel bag on my shoulder with one hand and held my pants up with the other. It was great to be on solid ground again.

From the troop ship we boarded trains and headed south. We passed an endless stream of orange tiled houses and before long I was asleep. The best sleep in almost ten days. Eight or nine hours later we detrained and were assigned to barracks in Kaiserslauten, ready for assignment to various 7th army units in southern Germany. We were notified that the next day was Passover and Jewish soldiers could sign up for a Passover seder to be held at a nearby air force installation. In a somewhat semiconscious state I took my first real shower since leaving New Jersey. The water was ice cold but at last I felt clean.

In a wrinkled class A uniform I boarded a bus with about 25 other Jewish guys and traveled an hour and a half to the “nearby air force Installation”. It turned out be what is now Ramstein Air base. There were over 200 men at the Seder conducted by a Jewish chaplain, who most of us couldn’t hear. No P.A. system… In 30 minutes I was sound asleep, food uneaten. A gentle nudge 2 hours later got me up and on the bus back to the repo-depo. Next day was my real fully conscious day in Germany. Without any particular duties, I went to the PX, bought a can of pipe

tobacco and saw my first general.

On the third day off the ship we were interviewed for assignment. Along with about 30 other guys we were trucked to the headquarters of the 39th Infantry regt., the 9th infantry division in Nurenberg. Thus began my career as an army medic/ part time pharmacist. Artie Weisbart was also assigned to the 39th. He became a medic with the 2nd battalion in Zirndorf and I was assigned to the 3rd battalion in Fuerth. Each infantry battalion had a medial platoon attached to provide field medics and an aid station for casualties evacuated from the field.

When I arrived at Monteith barracks, home of the 3rd battalion, the troops were In the field. Someone pointed to an unused bunk and said, “take that one”. I drew some bedding from the supply Sgt., undressed, and slept for 12 hours. The next morning I woke with this huge guy standing over me. He looked down and said, “ are you Jewish”? This was my first greeting in Germany. The hulk turned out to be Shelly Krauss, my buddy for the next 15 months. He read my name on my duffel bag and assumed the obvious, another Jewish G.I. had arrived in the land that Hitler tried to rid of Jews.

How ironic, that the Monteith barracks entrance was located on Jacob Wassermann

Strasse.

Wow! Germany.................there’s a lot of remembering,….. being in the U.S. Army in Germany.

In 1955, Nurenberg was still partially in ruins following the allied bombing during WWII. What had been the old walled city was being rebuilt from the rubble. The most pervasive sounds were those of the putt-putts of motor bikes. The color of men’s clothng was either a shade of brown or ashy gray. Woman’s clothing still reflected the styles of the pre-1940 era.

Nurenberg had been the scene of a great deal of Nazi official activity in the 30s and early 40s. A giant stadium had been built in which 10s of thousands had rallied to Hitler and his monsters. The stadium minus its huge swastika still stood. In 1956. the stadium was actually the site of a world Jehovahs Witness convention. Ironically, Witnesses had been one of Hitler’s targets for extermination.

The Palace of Justice, where the 1946 Nurenberg Trials had been held, was our synagogue. The second floor, just above the courtroom was where we gathered every Friday evening for Shabbat services. Our rabbi, chaplain Pincus Goodbatt, would start each service with, “ know where you are”. The hundred or so of us knew what he meant. If the Nazis had succeeded, it was unlikely that we would be there. This was my first experience as part of an organized congregation of Jews. It was an introduction that has had a lifelong profound effect on me. I have never been embraced with the spiritual part of being jewish but I am a part of the Jewish community and the Jewish people.

The army is a very structured hierarchy in which officers and enlisted persons do not socialize. Friday evenings at Jewish services was a very obvious exception. At one point, my battalion commander filled in for our cantor. He was a West Pointer with a great voice. In the preparation of our oneg Shabbat, officers, their wives and us lowly grunts all pitched in to prepare kosher salami sandwiches. We did maintain decorum to the extent that we always respected rank, never

treating our fellow Jews who were officers disrespectfully. We ranged in rank from privates to several majors and Lt. Colonels.

It took very little to convert me into a European tourist. It was hard to imagine, getting on a bus, and 6 hours later, being in Paris. It was the first of many times I would visit the city of lights. Between visiting the countries of western Europe, I managed to spend some ”delightful" weeks in the field with my medical platoon. For months, we spent two weeks in the field and one week at our base, alternately. These caombat exercises were in all kinds of weather and took us almost to the communist Czech border. We spent many happy days in a heavy weapons impact zone called Hohenfels.

Everyone was issued a weapon, even the medics. As soon as we arrived at our bivouack area I tucked my carbine in the back of our truck and settled into the field routine. I learned a lot from some of the “old” soldiers. Some had been in WWII or Korea and some in both wars.

Some Nurenburg sites: Billingenlangen strasse was my trolley stop…. The Americana club was the G.I’. s downtown service club. The Haupt Banhof was the main train station and schatse strasse was the other service area.

Regimental headquarters was located on a former german airforce base. The airfield was bordered by farms whose buildings housed families and the family cows. They were separated by a thin wall. The house of course smelled like a barn but the cows kept the house warm in winter.

Cow & human manure was collected and placed in giant wheeled vats that we called ‘honey wagons”. The wagons were horse drawn and used as fertilizer for the crops. All of our fresh vegetables came from Denmark where they didn’t use human manure.

One unpleasant day, one of our jeeps collided with a honey wagon. The odor was unimaginable. The jeep and its occupants were completely covered in shit. The M.P. s stopped the jeep at the base entrance and kept them there til the base fire company made the jeep’s occupants remove all of their clothes and hosed them and the jeep down. The clothes were burned on the spot and the Jeep was taken to the motor pool and repainted. I never found out what happened to the

honey wagon and its driver.

Our aid station acted as a VD clinic and treatment center for minor illness. A padlocked cabinet contained our supply of morphine syrettes. Each was like a tiny toothpaste tube with a needle at the end and containing 15 mg of morphine. The morphine was to relieve the pain of combat wounds and injuries. There were 24 syrettes which could not be secured when we were in the field. Most of the time the syrettes resided in my fatigue shirt pocket.

Cordon Bleu was a NATO exercise in which thousands of troops and vehicles all over western Germany were involved. I was sitting in a medical vehicle on top of a hill and as far as one could see, there were trucks, and armored vehicles. What a sight.

The Jewish chaplain, Rabbi Goodblatt, was affectionately called Pinky (Pincus) by his wife. During our too frequent outings in the field we were usually accompanied by chaplains of various denominations, except “Pinky”. Some of us convinced him that he should visit with the troops for a few days. He loved the idea but Mrs. Rabbi was less than thrilled about her husband being out in the elements. Finally, we got him into field gear and had him join us. Those few of us who were Jewish swelled with pride at having our chubby little Jewish chaplain with the star of David on his collar, out with troops.

I’m finding my rememberances are like a long lost archive with lost treasures that reveal themselves, one memory leading to the next.

An interesting Nurenburger was a photo shop keeper I met soon after arriving at Montieth Bararcks. He was captured by U.S. troops in North Africa and shipped to Kansas for the duration of the war. He liked America but wouldn’t allow his daughters to date G.I.s.

Other than soldiers or civilian U.S. army employees, the only other Jews in Nurenberg were displaced persons from from eastern Europe. I never figured out why they hadn’t emigrated to Israel or the U.S.

Passover seder1956 was held at the Hotel Grand in Nurenberg. All jews, military and civilian, and displaced persons living in the area were invited. It was an event that had not happened in that city for at least 25 years.

An interesting site was the Kirscheplatz in the center of Nurenberg. In the square, in front of the church was a monument which marked the building and the burning of a synagogue not once but twice in 200 years.

In mid April of 1956, Shelly and I and a Lt. named Ira Gewertzman drove to Italy and back through the French Riviera, just when the Grace Kelly wedding happened in Monaco. We saw the procession coming down from the church, Kelly and the Prince in an open Daimler Benz.

Long before the European Union, we could travel all of western Europe with an Army I.D. card as our passport.

I didn’t save any lives but I did get in trouble trying. A man on a motorcycle collided with a small truck almost at the entrance to Monteith. Medics in the aid station were called out. The man’s leg was wedged between his cycle and the trucks body. He was screaming, obviously in great pain. I ran back to the aid station and got a syrette of morphine and injected him. The civilian ambulance arrived in about 15 minutes and I thought that was end of that.

Several days later, I was ordered to my company commander’s office and really reamed out. I was not supposed to inject a civilian with morphine or anything else for that matter. I meant well. If the injured man had been a G.I., it would have been OK.

Officially, the allied occupation ended in June 1955. Thereafter, we were guests of the German Democratic Republic. Actually it meant very little to most us. Rail travel had been free when we were occupiers, now we paid regular fares.

Each company had its own mess hall. Medical company was the most desirable of the regimental mess halls. Somehow our mess sgt. transformed army chow into special meals. The army was trying to discharge him. because he exceeded the mandatory retirement age. There was a rumor that he had enlisted during WWI in 1918. He was at least 55 years old. Poor guy, the army had been his home for over 35 years.

Sgt. Bartram was our platoon sgt. He took a real dislike to a few of us. Shelly Krauss was on top of his shit list. Every time we went on leave, Bartram was waiting for us to get back late. We never accommodated him. I’m sure he had all kinds of punishment planned for us.

The guy with highest I.Q. in the regiment was Rodney Harrington, a tall lincolnesque looking New Englander. Everyone liked him. He later went to Veterinary school and moved to Australia.

My first official experience in medical company was being part of a duo to return a soldier named Pelkie to the company from the division prison. He had a congenital disease called thievery. would later find out that he would steal and sell anything not bolted down and under guard. He had been caught stealing coffee from our emergency in-field rations and selling it on the black

market. On the other hand, if you needed something not readily available, Pelkie was your go-to guy. Some months later, they made him the movie theater manager. Go figure it out. His special friends never paid admission.

In the summer of 1956, Artie and I travelled by train to Hamburg, and rented a Volkswagon. We took a ferry to Denmark and drove from there to Norway and Sweden and back to Copenhagen. We covered over 2,000 miles. I did all the driving. Artie didn’t know how to drive.

When the soldiering and touring had run their courses I became a short timer. With only weeks to go, I started to count the days when I would board the troop ship at Bremerhaven and head home. Even after being away for 17 months, going home was full of trepidation. Uncle Sam fed me, clothed me, housed me and had put a few dollars in my pocket. Now I had to face a whole new life. I had a college degree but I was sure that I had forgotten everything I learned in college. I did miss my folks, but had become very comfortable with the army and living what I considered the good life.

The voyage home was something I didn’t look forward to. Though, I must say it was a lark compared to the voyage to Germany. Guys I ate with every day, shared field duty with, played cards with, would soon be dim memories. I often wondered how life would play out for them.

The ship to Germany was the Buckner and the ship that took me back to the states was called the Bruckner. I did go up on deck to catch sight of the Statue of Liberty as we passed on our way to Staten Island and terra firma. We were bused all the way to Fort Dix from which I had to bus back to N.Y. and see my family for the first time in almost a year and a half.

Becoming a civilian was not easy. I was discharged, given about $200 mustering out pay and was looking for a job 3 days later.

A silver star of david on a chain around my neck disappeared on the first day at Fort Dix in Oct. 1954. It was a bar mitzvah present from my cousin Sylvia. On my second day home, 2 years later I was trying on some of my civilian clothes when out dropped my star and chain from the cuff of the trousers I had been wearing when I was inducted. I’ve been wearing it all these years later.

I called a few girls I had dated before the army. They were all married or in serious relationships. My bellhop friend, Stan Brandt had just been discharged from the Coast Guard. Artie was also job hunting. Shelly Krauss got a job as a liquor salesman. Mario had become severely alcoholic and his business was crumbling around him. When I saw him I was almost in tears. Joe Horowitz was still operating his pharmacy but the neighborhood was changing rapidly and my teenage refuge,

the hospital, had closed and been converted into a yeshiva.

My dad was working for a butcher, just getting by. Getting a pharmacy position had taken a new twist since I’d been away. It was almost mandatory that I join union local 1199 in order to work. So I joined. It was a rather benign union whose president was Leon Davis. Davis was a pharmacist and a socialist. His salary was pegged to the union wage for his pharmacist members.

My body was back in Brooklyn but my mind was still in the army. I applied for jobs, was hired and left after a week or so. In one case I worked for 2 brothers, one of whom was stone deaf and the other had migraine headaches. I decided that I would stick with the next job no matter what. The next job was Delta Pharmacy in the middle of one of the most violent neighborhoods in Brooklyn.

My boss was Murray Zeiler, a WWII and Korea vet. The pharmacy didn’t provide a very professional atmosphere. Not many prescriptions but lots of condoms and hair pomades. I soon learned that Zeiler had shot and killed a guy during a hold up of his pharmacy. When I closed at night a local cop usually walked me to my car.

The shooting had instilled a certain wariness and respect from the locals. Over the months I came to know a whole different culture and a lot of interesting characters. A whole day would go by in which no white person entered the pharmacy. In a way, I was a novelty to folks who came to the pharmacy.

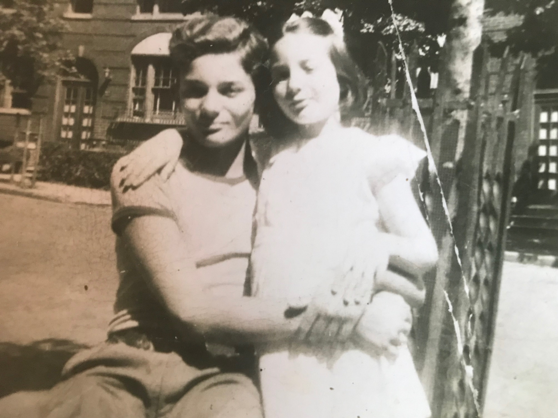

One April weekend, I had a date in Laurelton and met my Angel, Beth. Corny but true, it was love at first sight. She came to the door wearing a blue print dress and I was smitten. It was a double date with Stan Brandt, my old Bellhop buddy and his girl friend.

The next day, my dad drove me to work. He asked about my date and I told him that I was going to marry Beth. He thought I was crazy. Six months later we were married.

Meeting the prospective in-laws was daunting. It happened on a beautiful June day in Asbury Park, N.J. where Beth’s sister was graduating from a fancy private high school.

My first meeting with dear, sweet, mother-in-law and my best friend forever father-in-law went something like this: I said, "I love Beth and she loves me and we’re going to get married”. And we did marry 4 months later.

That is what I remember of the first part of my life.

I was eleven years old at the first Family Circle meeting. Much has happened since 1943. For those who may be interested I will happily update you with the more recent events in the life of the Bridgeton, NJ Wassermans.

As a retired person I have lots of time to ruminate. Beth and I spent 35 very fulfilling years operating our pharmacy. When that phase of our lives ended there was a short while in which I had to reinvent myself. I can report that there certainly is life after the pharmacy.

We've had the opportunity to really know our children and grandchildren. For those who do not know, Keith is our oldest at 44 and is a stay at home super-dad who does independent, commercial promotional videos. Keith and Betsy are the parents of Aharon, 16, Jacob 12, and a very delightful Isaac age 2 and 1/2. Betsy is a PhD human relations person with the Univ. of Pennsylvania Health System.

Roy is 42 and married to Wendy Foster and they are the parents of Ben, almost 12. Roy is a lawyer with the NY Legal Aid Society. I can hardly believe that he works in, of all places, Brooklyn. Go figure it. (New baby due in November ’03.)

Pam is 37, married to Dan Adcock, our favorite son-in-law (our only one). They are mom and dad to Sam, age 3 1/2. They live in Silver Spring, Maryland. Pam is the education director for Population Connection a non-profit environmental organization. Dan is the legislative director for the National Association of Retired Federal Employees (NARFE).

Beth and 1 are married for 46 delightful years. Her dad, a retired physician is 96 years old and lives with his 92 year old second wife. They are a cool couple and provide us with a wonderful connection to this community. Having practiced over 50 years in Bridgeton, he is much loved and respected by everyone.

Without boring you with the details, it’s been a good life.

Lenny Wasserman

}}

}}

}}

}}